Paris Photo 2024: A Return to Elegance, Where Beauty and Inquiry Triumph Over Sensationalism

- Zoe Chambers

- Nov 11, 2024

- 5 min read

The 2024 edition of Paris Photo has returned to its traditional home in the Grand Palais, a venue as regal as it is challenging for logistics. While its substitute, the Grand Palais Éphémère, offered the ease of nearby hotels, cafes, and restaurants, Paris Photo’s decision to reclaim its original grandeur signals a commitment to the sublime over the convenient. Art, after all, thrives in spaces that offer room for contemplation rather than ease of access.

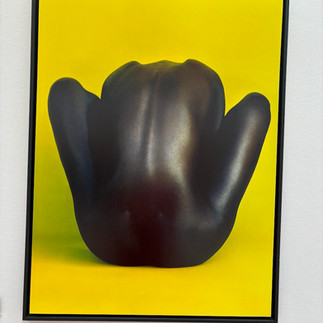

This year, the fair embraced a sense of spaciousness both physically and artistically. Wide aisles allowed visitors to move freely, without the shoulder-bumping bustle of past years, while large, open booths provided enough room to appreciate each work at a comfortable distance. For the first time in years, the fair also seemed to dial back its more provocative themes, presenting a version of contemporary photography that felt, quite simply, more polished. Extreme nudity, raw violence, and gritty urban scenes gave way to subtler, often naturalistic works. This shift points to a move toward a more refined aesthetic, blending craft and collage with photographic art in fresh ways.

Photography, once rooted in documentation, seems to have reached a point where it’s looking back to fine art origins in order to move forward. After a period of experimentation, it now seems to be revisiting its early role as a straightforward art form, distinct from its more experimental, conceptual and documentary applications. This shift mirrors the dynamic seen at major art fairs like Art Basel Miami or London’s Frieze, where photography now blends seamlessly with installations, mixed-media works, and other contemporary art forms.

The absence of several long-established galleries—like Halcyon, Timothy Taylor, and Yancey Richardson—reflects this change in direction. Replacing them are major contemporary art galleries, including Gagosian, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, and Pace, suggesting a growing intersection between traditional photography and the broader world of modern art.

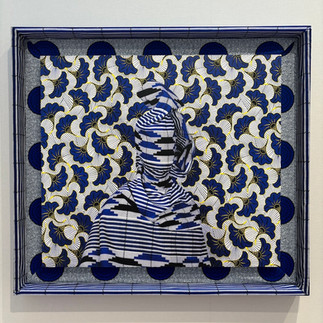

Collage-based works, often set within 3D dioramas, offered their own meditations on form and history. Among the most engaging was South African photographer Lebohang Kganye’s diorama series, which transformed familiar photographs into narrative tableaux. The exploration of new media for photographic printing added further dimension. Young artist Yunya Yin’s work, for instance, featured a photograph of a seashell printed on an unconventional material, providing a novel twist while raising intriguing questions about conservation and durability.

For those who appreciate discovery over prestige, this year’s fair offered plenty to savor. A standout was booth of Galerie Julian Sander from Cologne, which dedicated an entire wall to People of the 20th Century, a project by the foundational documentary photographer August Sander and also a great grandfather of Julian. The series, totaling 619 gelatin silver prints, was created from original negatives by Sander’s son, Gerd, in the 1990s. Mounted en masse, the display achieved a breathtaking balance of magnitude and intimacy, inviting visitors to explore each photograph individually while appreciating the cumulative power of the whole. It was a triumph of curatorial vision—a tactile encounter with history and humanity that set a high standard for documentary display.

Paris Photo’s international reach remains one of its highlights, with galleries from Bogotá, Shanghai, Taipei, and Buenos Aires presenting an invigorating diversity of styles and histories.

Works from the early to mid-20th century captured the attention of many collectors, with pieces from the 1930s to 1970s drawing significant admiration.

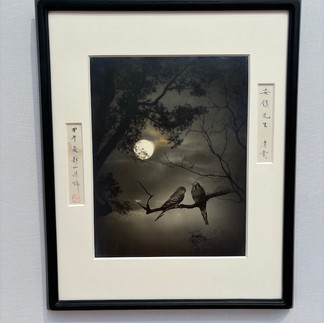

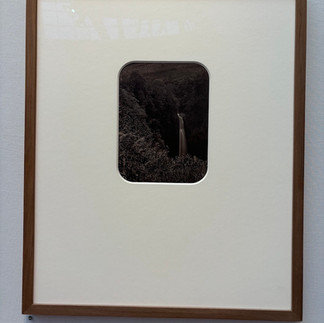

Taipei’s Each Modern gallery showcased Talking Water in Dawn from the River by Taiwanese photographer Lang JinhShan. The 1930s photograph captures the delicate, ethereal qualities of classical Chinese painting, blurring the line between a photograph and an ink painting. Its surrealist qualities added a sense of depth and significance to the fair’s presentation of historical works.

At this year’s fair, Lumière des Roses from Montreuil provided a welcome return to that era, exhibiting documentary pieces that felt as relevant and resonant as when they were taken.

Presentation was equally striking, with gallerists using inventive methods to frame and display pieces. However, some booths also highlighted the tension between innovation and imitation. Galerie Bilhalle, for instance, showcased large-scale photographs like by H. Kerstens or Ilona Langbroek that emulated famous paintings by artists like Hans Holbein and Vilhelm Hammershøi,. While visually impressive, these works leaned too heavily on replicating the compositions and techniques of past masters, blurring the line between homage and imitation. Similarly, Marie Cloquet’s Earth series, represented by Galerie Annie Gentils, attempted painterly mimicry, which, though visually striking, felt more like an imitation than a fresh interpretation.

This trend toward photographic emulation brings to mind photography’s “golden age” from the 1920s to the 1960s, when artists like Robert Doisneau, Man Ray, and Nadar transformed photographs into poignant, soulful artifacts.

At this year’s fair, Lumière des Roses from Montreuil provided a welcome return to that era, exhibiting documentary pieces that felt as relevant and resonant as when they were taken.

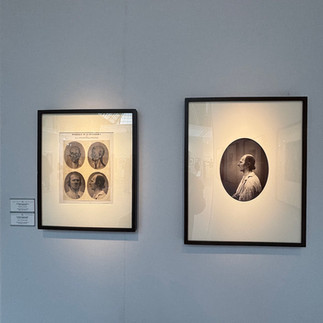

A hidden gem of the fair was Parisian Gallery Bruno Tartarin, specializing in rare and anonymous vintage prints. Highlights included a lenticular series by Maurice Bonnet and a 1915 strawberry still life on glass. These pieces reminded visitors of photography’s quiet magic and historical value.

The fair’s centerpiece was booth of Fraenkel Gallery which represented Hiroshi Sugimoto, showcasing his minimalist portraits and abstract works. At its heart was a new piece, a 2024 photograph of Mount Fuji printed on traditional washi paper and mounted on a Japanese folding screen. This combination of old and new felt both timeless and bold, bridging tradition with modern methods.

Another noteworthy Japanese artist, Rika Noguchi, presented a peaceful series titled Small Miracles, adding a sense of calm to the fair.

However, one disappointing change in life of Art Fair was the lack of a printed catalog this year, a staple for many visitors to Paris Photo. Perhaps, as the saying goes, “Manuscripts don’t burn,” but their absence was certainly felt.

After hours meandering through this year’s fair, it seemed clear that the overall scale has indeed shrunk. Walkways were wider, booths fewer, and the frenetic energy often associated with Paris Photo had softened into something more measured. Gone were the endless lines for cafeteria, champagne bar and for access to the special exhibitions. Though there were queues at the entrance due to a reduced security presence, inside, the atmosphere was tranquil—a refreshing shift from the loud, often unsettling world of contemporary art’s recent years.

And did this more restrained format detract from the experience? Hardly. Quite the opposite. It feels like Paris Photo has embraced a new chapter, one where beauty and inquiry triumph over shock and noise. The result is a serene, spacious art world more interested in the soulful and the subtle than the sensational. Here’s hoping this evolution continues.

Comments